Those who use academia to learn a craft, only to step out and use the craft to reinvent an equitable process of getting things done in the real world, restore my faith in education. My study of their work (918 Dill Ave) is to get a closer understanding of what such translation means and to document similarities and takeaways for my work.

Adapted from conversations with The Guild.

This is 918 Dill Avenue. It is the Guild’s first project. Antariksh Tandon, who explained the project to us, is the Director of Design & Development at The Guild. Avery Ebron, who joins us a little later, is the Director of Community Engagement and Operations. They start by giving us a broad overview of what they do and then go on to discuss details such as the ownership model and some of the legal and economic frameworks undergirding the models.

The Guild was started in 2015 by Nikishka Iyengar. It was started to address the racial wealth gap predominantly between the northern and southern parts of Atlanta. Real estate is the primary way to build wealth in this country, a process from which black and brown folks have long been marginalized. Nikishka started her work by turning her own house into a co-op. She lives in East Atlanta, which is on the opposite side of town from here. From there, The Guild expanded into managing some cooperative businesses and seven units in somebody else’s development, an affordable housing asset.

Very quickly, they realized that in their work, when partnering with the developer, who gets to dictate the terms of capital, you are beholden to the capital project, and you have very little agency over how properties are designed, owned, and operated. So the team caught themselves inadvertently becoming a real estate company because of this limitation of the dominant methods of standard Real Estate practices.

918 Dill Ave has suffered many, many delays as a result of The Guild’s experimentation and attempt to redesign a Real Estate model that was equitable and that could function within the legal systems. The project was started in late 2020 when the team got a grant to acquire the property at 918 Dill Ave. At the time, the idea was to build permanently affordable housing in a building that would be owned by the people who lived in this neighborhood. To be exact, the property was going to be owned by people within the zip code.

With the grant secured in 2020, the idea then was to really take real estate off the speculative market and also put the agency back in the hands of the people who live in the neighborhood. One of the things they would constantly hear when they engaged with people in these neighborhoods in southwest Atlanta was that they felt this lack of agency in determining what was happening in their neighborhoods and being able to participate in any change in their neighborhoods.

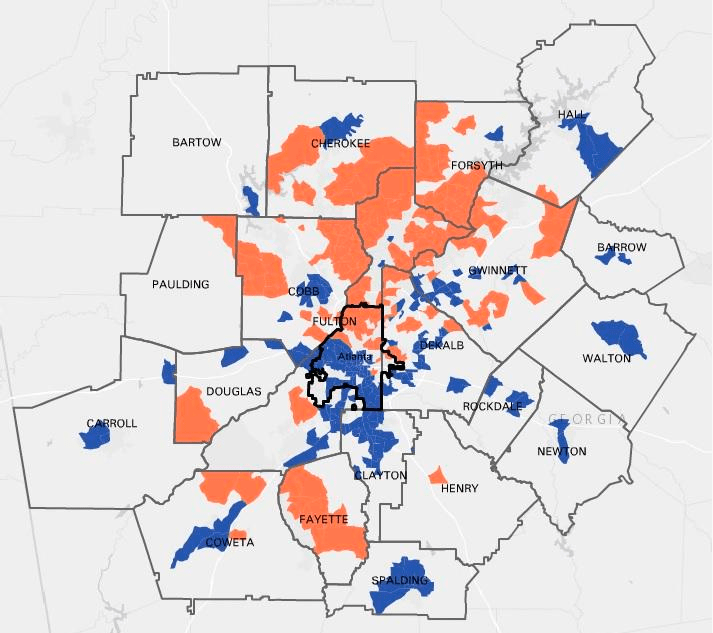

https://www.wabe.org/map-atlantas-highest-and-lowest-income-neighborhoods/

For context, Southwest Atlanta is everything west of Highway 75 and 85. Historically, everything south of Highway 20 is southwest Atlanta, where black and brown folks, but predominantly black folks, have been pushed into over the last century. This is also where capital has steadily left for the last century. But after decades of disinvestment, capital is now flooding back in and returning to these regions. This is a story of a lot of American cities. However, this new capital is to blame for the likes of about 300-unit housing projects that are built completely incongruous with the scale of the neighborhoods in this area. The developers of these projects are mostly national developers or generally developers who operate at the scale of the entire southeast region. They are not, and understandably, owing to their scale, don’t find the capacity to connect with the neighborhoods they build in. More on the capacity required for this task as you read on!

There was a capital return which led companies like Range Water or Greystar to build a lot. The developers live in Buckhead, which is in northwest Atlanta and is known as Atlanta’s secessionist neighborhood. They have a strong will to break away from the city of Atlanta because they don’t like that their tax dollars are going to black and brown households who share property tax jurisdiction with them.

To follow suit, when developers from such neighborhoods work in southwest Atlanta, people question development, and understandably so. Beyond that, they are helplessly locked out of the changes in the neighborhood as the development functions within a capitalist and speculative Real Estate Market that they are already predominantly priced out of. They have no ability to participate in the development of their neighborhood. A lot of them end up getting displaced.

The neighborhood has been gentrifying for a long time. How does The Guild take precautions?

“For us, there’s this thing where you definitely want to make the right decision. But most definitely, we want to ensure we don’t step into a pit and make the wrong decision. That’s a really tough space to be in, in development, where doing a really bad thing is ten times worse than maybe not doing something right. So we wouldn’t be one to grab a building that would create a political or neighborhood controversy. And that’s definitely something to consider when stepping into this type of work carefully. It is important to want to know and to do something about such possibilities early on. And if you don’t, you know, you’re in trouble.”

Avery, The Guild.

Before closing on the 918 Dill Ave property, the team at The Guild started talking to the Neighborhood Association and the Neighborhood Planning Unit. Atlanta is broken up into 25 Neighborhood Planning Units, or NPUs. They are the only set of citizens’ bodies recognized by the municipal government as being sanctioned to give feedback on development projects to the city. For instance, anytime you’re developing anything in any neighborhood in Atlanta, you’re supposed to present the development in front of the Neighborhood Planning Unit as part of the planning permit requirements. The neighborhood will then vote to approve or disapprove of the project or say they are going to defer voting on the project. Therefore, until they can resolve a few of the conditions posed at the meetings and go back to the NPU with updates, they might not approve the project.

For example, some concerns for the project may be that no parking is provided. Another concern may be about being able to build five stories, despite regulatory permits, and the mismatch between the scale of the building from the rest of the neighborhood and other such concerns. The City is not mandated to listen to the NPU and therefore only listens to them sometimes. Since they are not obliged to listen to the feedback from the NPUs, and really, whether they do or not depends on the project and the political narratives within which the project is embedded, the NPU system is a good idea executed poorly. Oftentimes, the people voting on the projects are residents of the neighborhoods who are not super informed about the projects.

The Guild does a lot of outreach before NPU meetings to make sure that people are really aware of what the projects are. Despite the fact that this outreach is discounted by the municipal government and the City government, it is an integral process in The Guild’s method of working. Although there are issues with the NPUs, it is also one of the only ways that people in the neighborhoods do get to effect change. Meetings often get taken over by certain groups of people who want to be in power, for example.

In an attempt to really tap into the grant for the project and learn from the community, the team reached out to meet the neighborhood associations and ask them about what they wanted to see here. One of the first things we heard was that the neighborhoods lacked fresh produce. There is no fresh food anywhere close by, having to go to the west end to get a hold of fresh produce. And so the team decided that they were going to put in a small grocery store in the front, first thing as you enter the building on the first floor. This raises all kinds of complications relating to scale. Grocery stores in the United States are predominantly bigger than the entire building on 918 Dill Ave. But the team paused to imagine this use for the property. Grocery stores at this scale are typically harder to build and run because they cannot compete economically with a store like Kroger or larger chains.

“Grocery stores this small don’t come up often unless, of course, you’re in New York.”

Antariksh, The Guild

The other thing that the team wanted to make sure they did was to listen to the neighborhood about the kind of businesses they wanted to see. Something they told them is that they don’t really have any interest in having typical retail. Typical retail was somebody who paid a regular fee. The people of the neighborhoods were more interested in some sort of a membership-based system. So the remaining suites going towards the back of the building, on the first floor, are currently all going to be divided up, and a portion of it will be united into one large co-working space. A part of the walls in the existing building will be demolished, so there is a large event space.

“The success of a property really depends on engagement with the people who live in the neighborhoods, and allowing them to tell you what should happen with the building ensures that the project is going to be looked upon more favorably not only by the people who will be receiving it but also by lenders.”

Antariksh, The Guild

Typically, a project like this, at this scale, is not often built, especially in a context such as Atlanta. It is too small. For a typical development, considering what has always been done, the project is too small, with 18 units of affordable housing over top of the multi-use commercial space on the first-floor level. This is the scale of buildings that have not been built because economies of scale don’t work well in such situations. The rules of the game change entirely and need to be reconstructed to create the realities that The Guild would like to design. However, when the team approaches construction lenders, they say, “look, the neighborhood is really interested in seeing something like this,” and provides them with a set of data points and other things that bolsters confidence in project members.

“It becomes critical to note that this is one of the trendsetting qualities of The Guild; they lay a foundation for organizations that aspire to do similar work to make neighborhoods more inclusive. They take their respective educations and expertise in domain knowledge to think critically about its translation into working methods to realize projects in the real world. The example fits well into an entrepreneurial model that is socially conscious, educated, aware, and consistent in its team effort to translate the concept into action.”

Vishnupriya, Author.

The above-mentioned strategies provide a meaningful way not only to have an impact but also to secure contracts to build the project. All this experimentation and hurdle-crossing took time owing to project delays. Starting in 2021, after closing on the property, they are (in early February 2023) hopefully only about six weeks from beginning construction; their timeline has been pushed out by nearly 12 months. Although this delay is partly because of the effects of a pandemic on the economy writ large, a lot has changed since the project began. Over the course of 2021 and 2022, the construction prices for the project went up by about $4 million for the notated design. What used to be about a $6.5 million dollar project is now a $10.5 million dollar project. This has caused the team to have to pause and sort through how to not only get additional funding and sort out finances but because the project is affordable to ensure that the program can meet its end goal of affordability and inclusivity in the region.

The construction loan that the project needs far exceeds the mortgage; the mortgage that a project can actually support is typically predicated on the rental revenue of the project. Since 918 Dill Ave has a low rental revenue owing to its affordability, the permanent mortgage can only be about half of what the overall construction loan needs to be. This caused the team all sorts of grief. However, The Guild is better now that they’ve solved that.

“There is more than one instance where you’re inspired by the way The Guild translates industry knowledge into work that helps realize their vision for an equitable city. Their many examples of hurdles and their narrative towards solutions make you believe that off-beat work can not only be visualized on paper but is built through collective effort, community engagement, and lots of resilience as a team. Sometimes, learning about and knowing the system is not just working at a day job to do what’s always done. But maybe you use your knowledge of the system to build new things, break inequitable systems of the present, and make them questionable for the future. The Community Stewardship Trust may have just been the invention that was waiting under their hats to be discovered in time.”

Vishnupriya, Author

Above was a broad overview of the economic life of the project over the last two years and the social conditions within which the project was embedded. But throughout the project, The Guild has intended to build the project and then transfer it into a Community Stewardship Trust.

The Guild’s primary motive is to de-commodify Real Estate. Their definition is that once built, a building must be owned cooperatively and never be bought or sold speculatively on the open market again. Although different people may have different definitions of de-commodification, this is The Guild’s.

The idea to de-commodify Real Estate, as The Guild puts it, stems from their belief that housing is a human right. They believe that housing is not an isolated good and that thriving neighborhoods need to have both housing and commercial property but more of such shared commercial programs built together, including things like grocery stores.

“Grocery stores were a need, and housing and commercial activities were a further pressing need. They realized the merits of combining these to make the economy scale for a venture such as this that was hard to come by and supported. They used the many loose ends of a project to create a building artifact that not only spoke to the residents but to the times we live in at present, in our broader economic, real estate, and legal structures.”

Vishnupriya, Author

The Community Stewardship Trust (CST) is our attempt at forming a cooperative entity that will own such projects in the neighborhood in the zip code that they’re building in.

After the project is built, the building will transfer into ownership of the CST. The building will be cooperative – it will be owned cooperatively by the residents of the building, so the resident does not theoretically own their condo or the apartment in which they live within the building, but they own a share of the overall building. They get to use the apartment they live in and solely use their specific living unit until they live there. Nobody else can come and live there while they are living there. But theoretically, what they own is the share of the overall cooperation. Similar to the concept of the co-op, the building is going to be owned by this cooperative entity, the CST.

People in the neighborhood will buy shares of the cooperative through the CST, and this allows them collective governance of the project. By creating the CST and transferring ownership to the cooperative entity, The Guild is trying to give the agency back into the hands of the people to determine the kind of businesses that get to be here. They have a say on what the rents are set at. It also allows them financial participation and agency because as the project depreciates in value, so do the shares. The community proactively gets to see wealth building through share price appreciation.

- A potential future article may address: What is The Guild doing to ensure that the community and the CST it forms have the capacity to handle financials to ensure continued sustenance of the building? How is The Guild making sure the people are ready? What does The Guild sense about the people’s preparedness?

As The Guild builds more and more projects in the zip code, and with every project they do, it enters the CST or ownership by the social trust, increasing the overall value of the trust. With this, the CST’s available opportunities for building uses expand over time. As properties within the trust increase in number, so does the valuation of the building, which adds to the appreciation, eventually leading to share price increases. Through this model, people get to see financial wealth building.

- A potential future article may address: Adding on to the previous question, is the CST prepared to handle multiple properties? Are there specific ways that the CST is set up to facilitate their establishment, initiation, and future growth that we can learn from? Could you describe the legal entity in greater depth?

One typically has to get an appraisal that tells them the proposed valuation of their project once it is built. A construction lender uses this appraisal value to give a percentage of it as a loan. This corresponds to the term loan to value, which is a construction lender saying, “We will give you 90% of the loan to value, which means if your project is going to be worth $9 million, we will give you $8.1 million, for example, as a loan.” This is the construction lender assessing that if things go south if the purchaser doesn’t make mortgage payments, they will be able to recuperate their money by foreclosing on the project because its values will give back a certain percentage of the investment.

“The value of the proposed project went up 50%. That’s just an indicator of how much land has been appreciated here and how much development enjoys, especially in southwest Atlanta. This is an obvious signal of why it’s so hard for people to continue to live in the neighborhood as their tax burdens go up. “

Atariksh, The Guild

What this project will be is the grocery store, a co-working space, three small kitchens serving lunch, the suites on the first floor, and two floors of permanently affordable housing of 18 units. In 2021, the project plan’s appraisal was $6 million. The property was purchased for $600,000. Prices went up over the 12-month delay. Since they weren’t able to close in funding right then and they had more than a 12-month delay, the construction lender asked them to get a new appraisal. In 2022, The Guild got a new appraisal, and the property is now valued at $9 million. Nothing has changed with the project. The Guild hasn’t done a single thing to the building. But the value of the proposed project went up 50%. That’s just an indicator of how much land has appreciated here and how much development has appreciated, especially in southwest Atlanta. This is a very clear signal of why it’s so hard for people to continue to live in the neighborhood as their tax burdens go up.

The 50% increase in the property’s appraisal value is the kind of financial appreciation that The Guild is trying to both help people participate in and also guard against through collective ownership of real-estate and passive wealth-building opportunities within the existing communities. Wealth building increases the resilience of people of color to participate equitably in developing their neighborhoods. Increased appraisals can have deleterious effects. The CST entity is meant to enable people to buy shares, and as the property goes up in value, whether it’s 50%, 20%, 5%, or whatever will be its appreciation, the shares appreciate by that much. Over the course of 5 – 10 – 15 – 20 years, even though people will be investing small dollar amounts, their commensurate share values appreciate with higher appraisals in the neighborhood.

For instance, in year one, The Guild plans to set their share price at only $10 per share. The idea here is that the households in the zip code don’t have a lot more than that to invest in monthly. This was arrived at due to using the area median income as an affordability metric. The Area Median Income (AMI) of Atlanta, which is the metropolitan region, is typical $96,000. At the same time, the area median income of the neighborhood of 918 Dill Ave, or its census block alone, is closer to $45,000 to $50,000. So it is about half of what the AMI of Atlanta is. AMI always skews higher because the higher salaries of a smaller group of people always end up skewing the number up. The AMI is just a straightforward mean and is not a weighted average.

If the AMI in 918 Dill Ave is $50,000 or closer to that, the median income north of Buckhead, which is where typical Developers live, is $250,000 a year. The density of those areas is about one house per acre. So it’s valuable land that will never densify because the people living there will protect it from happening. Essentially, AMI skews higher due to the small numbers of high median incomes in certain city sections.

All of the rents are set at 60% of AMI and 80% of AMI right now, and The Guild is aware that 80% of $96,000 is still much higher than $50,000. They are still skewing higher than they should be for this neighborhood. And that’s part of the difficulty of developing a smaller project like this is that the costs per square foot are just higher than they would be for the better unit project.

The Guild’s thesis is that projects like 918 Guild Ave are exactly the scale of projects that are necessary for neighborhoods like this, where people don’t get displaced by large monumental projects that have nothing to do with them or that they don’t have any ability to govern. And concomitant with that are issues of parking and mobility, and transportation. And all those are things one must deal with when working with community groups.

For instance, The Guild is not required to provide any parking for this project because of a few different things. One reason is the property’s position in the Beltline overlay. Half a mile on either side of the Beltline, affordable housing projects anywhere is not required to provide parking for the affordable units as a way to incentivize developers to build affordable housing. This causes people who live in those apartments, affordable apartments, to have to depend on MARTA. MARTA is a heavily racialized system in that it doesn’t go to a lot of Atlanta. And that is by design; it does not go further north, it does not go further east than if it is a place near the city. Highways and the MARTA in Atlanta were placed specifically to divide black and white neighborhoods.

One reason that people are excited about the 918 Dill Ave project is that MARTA is within a half mile from the site and is accessible by walking in about 9 minutes. At the same time, the MARTA only goes to a handful of places. This makes it really hard for people who need to travel extensively for work within the city to be able to do that. This needs to be taken into account.

It is not as simple as to say that a lack of parking is good and that people need to reduce car use because, in reality, cars do make a meaningful difference to people’s lives and their ability to have any degree of equitable, if any, access to their livelihoods and to thrive in American cities. This discussion splits the neighborhood up into different camps. Some people wanted to see no parking, whereas others wanted to see even more parking than we provide. All those discussions and deliberations add time to community engagement about the project, and the added time is expensive. This must be balanced for a productive effort to design affordable projects through active community engagement. All delays in time end with having to talk with the construction lender about why it’s taking so long. The Guild can not walk down with prices for things like the building materials that will be used because of time delays and added overheads and costs.

For the reasons explained above, The Guild’s way of working and building a cooperative model is an entirely different model of development than a typical speculative development model, where oftentimes developers will not even have closed on the property before they have their building permits. This is, so the developers do not have to wait on anything; they buy the property and get started as quickly as possible. This is a very large, broad overview of the whole project.

This blog post is adapted from the author’s conversations with Antariksh and Avery from The Guild. Many thanks to The Guild for their time and valuable insight on de-commodifying Real Estate as they describe it!

Leave a comment